Hello and thank you to the AFR for the opportunity to talk today about how we can tap into the rich resource that is Australian university research. I start by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land wherever you are.

I arrived in Australia from the UK in 2015 and feel privileged to now be a citizen of this great country. But I have been puzzled and troubled by the way Australia underestimates the value of its universities.

The extraordinary achievements and disproportionate impact of Australian universities was one of the main reasons I moved across the world to UNSW. Yet there’s a lack of awareness here of the far-reaching social and economic impact of universities and their research – and their incredible potential.

We have in them a unique national asset – not a burden, as some sections of Australian politics and media have us believe. The next decade – finding a path out of crisis – should be when that asset is fully realised.

The Go8 recently published a report “Enabling Australia’s Economic Recovery – through supporting research excellence”. The report made three recommendations.

Recommendations one and three: ‘Supporting excellent research at scale’ and ‘Transparent full costing of research’ – have my strong support, but the recommendation I want to highlight today is number two:

Sustainable translation and research infrastructure funding across national economic priority areas.

I cannot stress enough how crucial that recommendation is in helping answer our immediate and long-term challenges: a point recognised by our industry partners, including Business Council of Australia, and increasingly by government.

To inject a continuous flow of commercial and economic output into the national recovery, we have to drive the virtuous cycle of discovery, translation, application and commercialisation. Fortunately, we are strong in some aspects of this cycle.

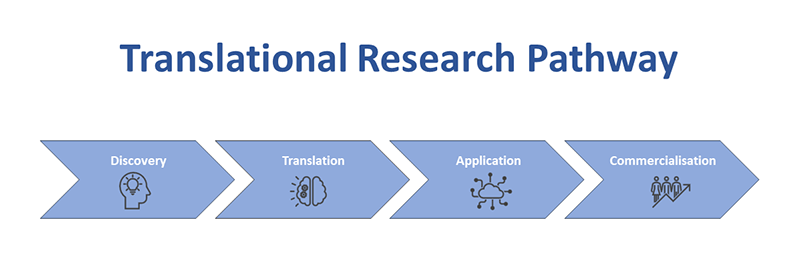

Global rankings are a measure of our research discovery output and excellence. Australia, with just 0.3% of the world’s population, has seven per cent of the top 100 universities and 4.7% of research citations. Per capita, we have more universities in the global top 200 than any other country with a population of over 20 million, ahead of the US, UK, China, Germany and Japan. On that metric, Australia leads the world and is a powerhouse of invention and discovery.

At the other end of the cycle, commercialisation, Australia has another strength, in the scale of our economy and the robustness of business and industry. We are close behind the US in GDP per capita, but our track record in connecting the discovery and commercialisation ends of the spectrum through translational and applied research is poor.

Part of this is to do with cultural issues and incentives. Our academics are incentivised and rewarded for world-beating discovery and not adequately for translation and commercialisation. And our economy is not structured with incentives to bridge the gap.

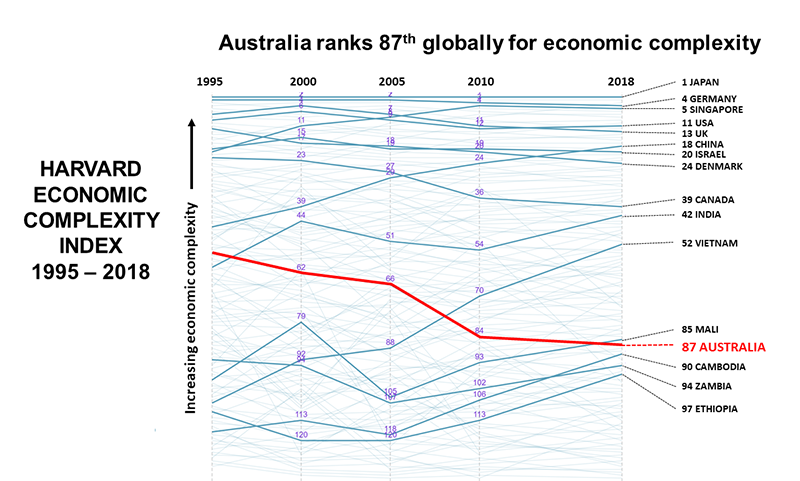

The Harvard Growth Labs' index of economic complexity and diversity is revealing. It shows that for economic complexity we are 87th globally, way behind most other OECD nations and sitting between Mali, Cambodia and Zambia. That means we have limited capacity to commercialise high-tech discoveries in engineering, science, design and health.

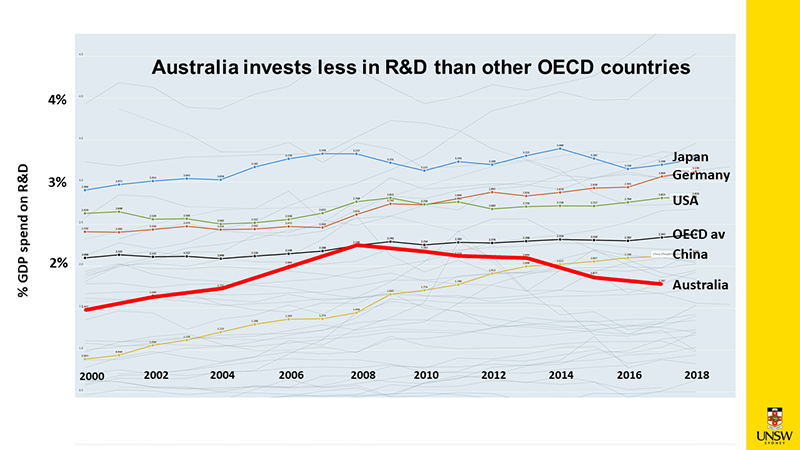

This is compounded by our failure to invest, as a nation, in R&D, which sits at just 1.7% as a proportion of GDP compared to the OECD average of 2.4%. Our competitors like China, the US, Germany and Japan sit at 2.1, 2.8, 3.3 and 3.3% respectively.

To match the OECD average would require an additional national investment of AUD $13 billion pa. To match Germany, Australia would need to double its R&D spend to over $60 billion per annum. The necessity to drive our economy out of the COVID-19 crisis means we cannot afford to ignore the opportunity waiting to turn a rich portfolio of discovery science into greater economic benefit for Australia.

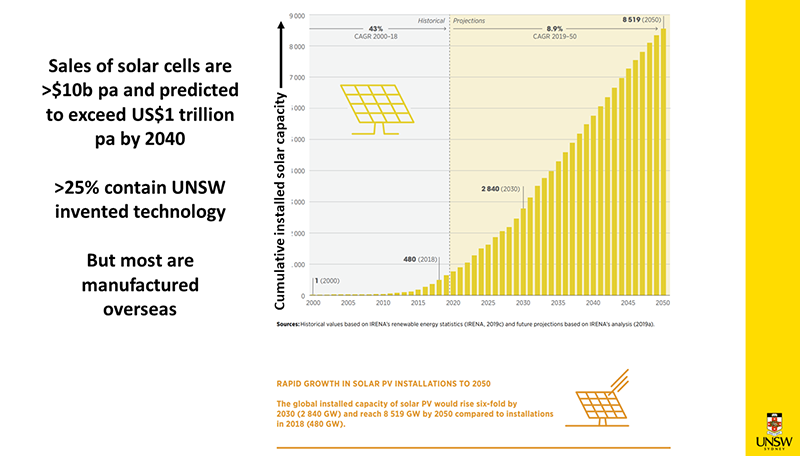

A classic example of opportunity missed by not getting the research pipeline right is the manufacture of solar cells, sales of which are predicted to exceed US $1 trillion by 2040. World-leading UNSW technology developed in recent decades is still in 50% of all solar cells worldwide yet, in 2001, no Australian investor could be found, and the production of the cells went offshore – as did significant economic benefit for Australia.

UNSW is now leading research in hydrogen for energy transition which will support Australia’s vision to become a major player in the global hydrogen market, and we are collaborating on next generation batteries that are low cost, safe and have high energy and power densities.

We cannot afford to forgo the commercial gains of such brilliant university research again. We need a major initiative to achieve much greater integration between the sectors and to bridge the gap between discovery and commercialisation.

The risk to the future of discovery research has been compounded by the funding profile of university research, highlighted in recent months by COVID-19. The sector and the government have become too reliant on international student revenue replacing public research funding.

The harsh reality is that we stand to lose our competitive edge if we do not act to support our research sector — a point made by The Australian newspaper recently. An editorial welcomed the Government’s reported plan to bring forward $750 million of university research funding from 2024-25, saying it is a fiscally responsible plan ‘to retain Australia’s hard-won expertise’.

That advance of funding will be a welcome response – but only a short-term fix. Frank Larkins and Ian Marshman estimate that one in 10 research positions may be lost by 2024 due to the decline in international student fee revenue.

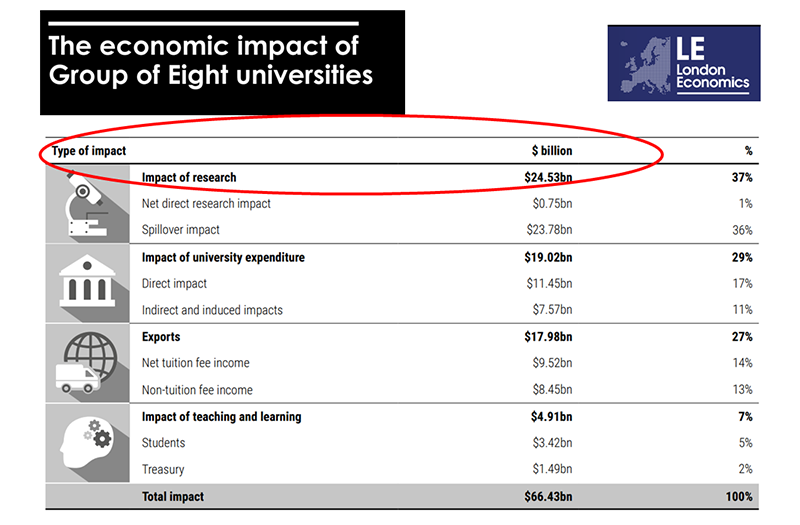

At present, the Group of Eight universities have an economic impact of more than $60 billion per annum to the Australian economy, of which $24.5 billion per annum is from research – a return of more than $10 for each dollar of public investment, creating thousands of jobs and opportunities.

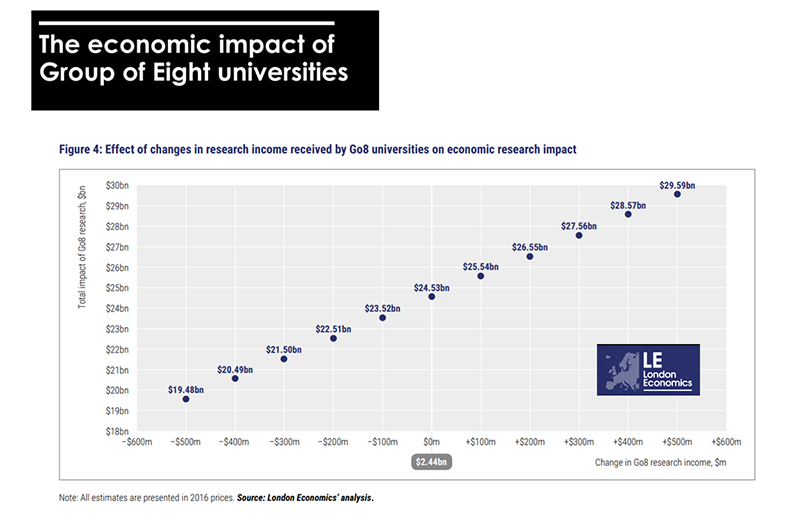

That economic benefit is highly correlated with R&D investment, and the potential to further greatly expand the economic benefit of the discovery – commercialisation cycle is at risk unless the investment is made.

We also need to consider the nature of the research we prioritise. Dr Thomas Barlow has recently released a research report, which I recommend to you, entitled The Future in Black and White, in which he provides data-driven predictions as to where opportunity might lie for the Australian university research sector over the next 20 years.

Barlow predicts that without a significant reallocation of resources and focus, “Australian patenting and inventiveness will continue to depend far more upon what happens in Australian industry than upon what happens in universities.” Barlow also sees partnerships between industry and Australian universities failing to flourish unless "… policymakers can give universities a real incentive to stimulate productivity growth."

If that eventuates, Australia will miss a massive opportunity to build on university expertise and drive a new high-tech and advanced manufacturing sector. But it doesn’t have to be the case. We can shift Australia to an economy which competes through cutting edge technology and services, especially in energy, AI, materials, health/medical, and advanced manufacturing.

So, in summary, we have a range of problems:

- A collective failure to understand the asset in our university research

- A lack of incentives in our universities for translational and applied research

- A lack of the diversity in our economy required to pick up and commercialise discoveries

- University research funding heavily dependent on student revenue

- A big hole in the national funding of R&D to drive the discovery commercialisation cycle.

We desperately need new sectors of the economy to drive growth over the next two decades. The Treasurer recently noted that a deficit of $200 billion is expected this year, dwarfing the $55 billion in the GFC, and gross debt has hit a record $787 billion. If we do not want to pass on these debts to future generations, we should look to invest in under-utilised assets for long-term return. University research is one such asset.

The evidence in Australia and around the world is clear – well planned and structured investment in R&D from a quality foundation generates large scale returns – look at Israel, Singapore, the US and Germany.

So how can we deliver this?

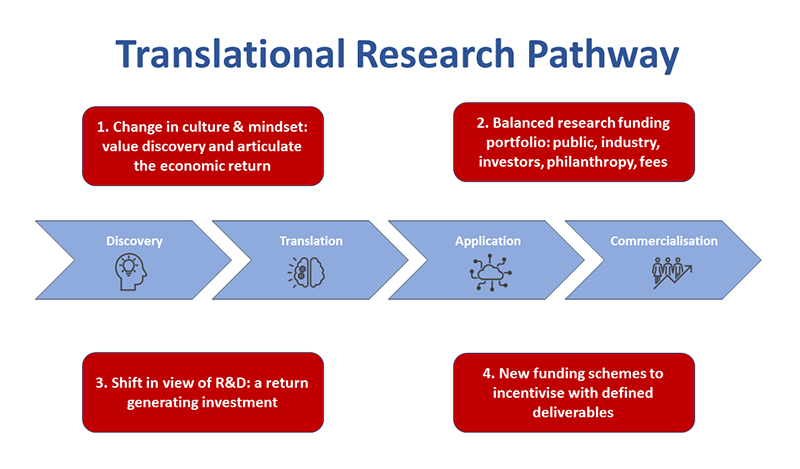

First, we need a wholesale change in culture and mindset.

Government, universities, industry and the media must recognise, highlight and encourage a national drive to secure the benefits of the discovery – commercialisation cycle. We need these sectors to work together in the national interest. The vision must be Australia as the innovation nation.

I will be interested to see more details of the Government’s manufacturing strategy that has been reported this morning. I hope it includes the incentives necessary to drive much greater collaboration.

Second, we need to quickly act to correct the unbalanced profile of university research funding which is not wise or sustainable.

The government has been only too happy to allow a gap in public funding for research to be filled by international student revenue – to a much greater degree than in the US, UK and Canada. A mixed portfolio of funding from government, industry, investors, philanthropy and student revenue is right but must be sensibly balanced. Achieving that balance will require additional public funding.

Third, we need to shift our view of R&D – it is a return-generating investment.

R&D spend needs to be seen for what it is – an investment to create powerful new industries. The BCA’s recent report from the ‘Playing to our strengths working group’, rightly highlighted the fall in total spending on R&D in Australia and recommended that Australia leverage research strength to achieve greater sovereign capability, underpinned by strong foundations in innovation, technology and advanced manufacturing.

Fourth, we need new, carefully planned funding schemes, specifically designed to address the challenges of incentivising universities and business, and to drive discovery to commercialisation with well-defined timescales and deliverables.

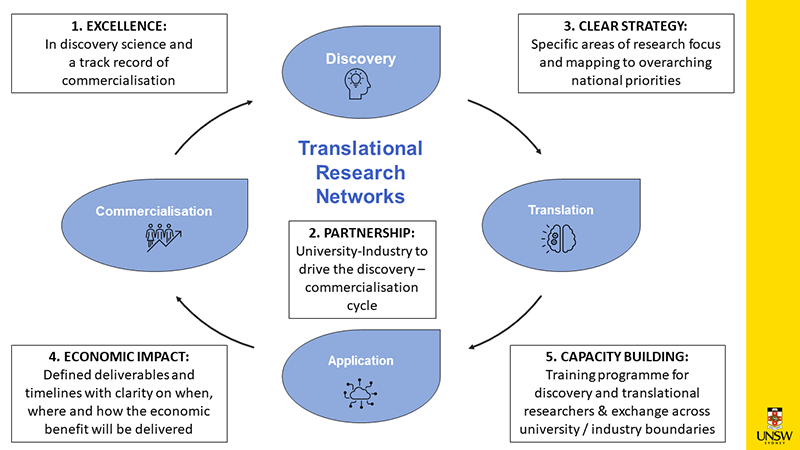

As part of that effort I favour a concept which I call the Australian Translational Research Network or ‘TRN’ scheme to drive a cycle of discovery – translation – application – and commercialisation. The scheme would require a new funding allocation filling some of the gap in R&D funding, but it would also harness and work with existing funding schemes. In some ways the TRNs would be the non-medical equivalent of the MRFF. But it would be much more explicitly structured around partnership to drive the discovery to commercialisation continuum.

I envisage eight to 12 TRNs across the nation accredited by government and funded long term to drive this cycle and establish a new era of research productivity.

Funding decisions would be based on long-term priorities and subject to external peer review. Government would set high level national priority areas as a framework – for example in energy, advanced manufacturing, health, defence, and space but there would be no micromanaging or captain’s picks on the detail.

Each partnership would decide where to focus within national priorities based on their expertise in discovery and their translational opportunities. Each TRN would need to satisfy an accreditation process spanning five requirements:

Requirement 1: existing excellence in well-defined areas of discovery science and through a strong track record of commercialisation.

Requirement 2: evidence of partnership. One university or a group of universities committed to working in partnership with industry and business and with CSIRO to collectively drive translation, application and commercialisation.

Requirement 3: a powerful strategic plan. Clarity on which specific areas of research excellence the TRN partnership will focus and how it maps to overarching national priorities. Detailed plans for delivery across the research cycle and the mechanisms to identify discovery research with translational and commercial potential.

Requirement 4: clarity about delivering economic value. Defined deliverables, timelines and check points providing clarity on when, where and how the economic benefit of the TRN will be realised. And of plans to lever university, business and investment funding to add to public funding.

Requirement 5: capacity building and culture. A well-defined training programme to ensure future generations of both basic and translational researchers and explicit opportunities for academics and industry staff to move back and forth across the academic/commercial boundaries.

The accreditation process would establish the TRNs with reference to lessons learnt elsewhere in successful ventures of this type in USA, UK, Germany, and Singapore. It would:

- Ensure high prestige for both academia and industry to overcome cultural barriers

- Be an open competitive award process with an international panel

- Provide funding long term – five-year renewable on hitting defined targets

- And funding at sufficient scale to deliver economic impact

The TRNs would need to link seamlessly to ARC, NHMRC and MRFF funded research and integrate with other public funds, with CSIRO, industry resources, tax incentives, philanthropy and investors.

I will finish with an example of a potential TRN in Sydney.

The NUW Alliance was set up three years ago to bring together the strengths of Newcastle, UNSW and Wollongong universities – to generate new social and economic opportunities for NSW. The founding universities are now working closely with Western Sydney University, the NSW government and Western Sydney authority, and industry partners to bring to life the Aerotropolis at the new Western Sydney airport.

The alliance will drive the translation of engineering expertise, as one component of a revival of advanced manufacturing in Australia, for industries including defence, materials and health at the Aerotropolis. It will employ a new approach to integration of vocational and university skills-based learning and eventually be co-located alongside industry partners at the airport precinct.

This is just one of many opportunities arising out of this national and global crisis, but we must act quickly and strategically to seize them. I believe that a network of Translational Research Centres across Australia with the passion, plans and resources to drive commercialisation based on research excellence can establish Australia as an innovation nation by 2030.

Thank you for your time this morning. I wish you all the best for the rest of the summit and look forward in hopeful anticipation to positive news on research investment in the budget next week.